Shelf Life

My intention is to hold stocks forever, but the harsh reality is every stock has different shelf life.

Saurabh Madaan talks about a new mental model for thinking about evaluating businesses.

One of my favorite investors is Nicholas Sleep of Nomad Investment Partners. He is famous in qualitative investment circles, but rather unknown to the rest of the investment world. He makes little to no public appearances. You won’t find much searching Google. He is a bit like Keyser Soze (movie: Usual Suspects) in that he is rarely seen but you know he is there.

Besides his incredible performance, the reason Nicholas Sleep is so famous is he not only invested in Amazon in the early 2000’s, but his articulation of his investment thesis was a masterpiece. A bullseye. It can only be read in his investor letters which are harder to find than a First Edition of Security Analysis.

The mental model he applied to Amazon fifteen years ago was called Scale Efficiency Shared, which he derived years earlier when investing in Costco. He would later change the name of the mental model to Scale Economics Shared after investing in Amazon. The best articulation and description of the mental model is actually described by Jeff Bezos in Amazon’s 2005 Investor Letter:

“As our shareholders know, we have made a decision to continuously and significantly lower prices for customers year after year as our efficiency and scale make it possible. This is an example of a very important decision that cannot be made in a math-based way. In fact, when we lower prices, we go against the math that we can do, which always says that the smart move is to raise prices. We have significant data related to price elasticity. With fair accuracy, we can predict that a price reduction of a certain percentage will result in an increase in units sold of a certain percentage. With rare exceptions, the volume increase in the short-term is never enough to pay for the price decease. However, our quantitative understanding of elasticity is short-term. We can estimate what a price reduction will do this week and this quarter. But we cannot numerically estimate the effect that consistently lowering prices will have on our business over five years or ten years. Our judgment is that relentlessly returning efficiency improvements and scale economies to customers in the form of lower prices creates a virtuous cycle that leads over the long-term to a much larger dollar amount of free cash flow, and thereby to a much more valuable Amazon.com. We have made similar judgments around Free Super Saver Shipping and Amazon Prime, both of which are expensive in the short term and – we believe – important and valuable in the long term.”

Businesses that fit this mental model choose to keep prices low, margins low and in doing so share their growing scale with their customers. Customers then reciprocate by purchasing even more goods or services from the company, which provides the company even more scale and more cost savings to share with the customer. This is the flywheel effect.

Scale Economics Shared is simple to understand, but it’s a hard concept for most value investors to buy into, especially in its extreme cases like Amazon. I talk about this mental hurdle for investors in this [Article]. Here is an excerpt:

Warren Buffett recently said, “We haven’t seen any businessmen like him [Jeff Bezos].” Which begged the question, “Well then why don’t you own Amazon?” which Buffett replied:

“Well, that’s a good question. But I don’t have a good answer. Obviously, I should’ve bought it long ago because I admired it long ago, but I didn’t understand the power of the model. And the price always seemed to more than reflect the power of the model at that time. So, it’s one I missed big time.”

Bezos just thinks differently than most people, including Buffett. In many ways, Amazon represents the opposite type of company Buffett typically invests in which is why he never bought it and likely never will. And to a lesser degree it’s why Berkshire never really owned a significant stake in Costco even though Charlie Munger sits on Costco’s board and adores the company.

In HBO’s recent documentary on Warren Buffett, Buffett talks about why he likes Coca-Cola and how the company and its affiliates serve 2 billion 8 oz servings worldwide per day. He says something like, “If you just get an extra 1 penny per day that is $20 million more profit per day, just 1 penny more”. I think that is a classic way he looks at a brand and its potential and to date it’s the opposite way Jeff Bezos thinks about Amazon.

But again, Amazon is an extreme case of Scale Economics Shared. You can find many successful and very profitable examples of this mental model going back a hundred years. For example, Henry Ford lowered the price of the Model-T seven years in a row to increase demand and production:

“Our policy is to reduce the price, extend the operations, and improve the article. The reduction in price comes first…the low price makes everybody dig for profits”. – Henry Ford

A few other investors have iterated on Nick sleep’s Scale Economics Shared.

Josh Tarasoff refers to it as the Volume-Price Virtuous Circle. Here is Tarasoff explaining it in his own words:

“Volume-price virtuous circle is when a company has a cost advantage, so it has a more efficient way of doing something. When you have a cost advantage, there’s two things that you can do. You can take more margin, or you can reinvest that cost advantage into the customer value proposition by lowering prices, by increasing service levels, by increasing product quality. There’s infinite ways to do it. It depends on obviously what business you’re in, how the best way to do it is, but you’re going invest [in a customer value proposition, and thereby grow your market share, grow your volumes, enhance your cost advantage. Then you go back and you invest further in the customer value proposition, and so on and so forth…. I think that’s very elegant and powerful when it’s done well. Familiar examples of this are Walmart, Costco, Geico, and the example from my portfolio that I’ll talk about is Amazon.” [Source]

A more recent iteration that I thoroughly enjoyed is from Saurabh Madaan, former Senior Data Scientist at Google and now Managing Director of Investments at Markel Corporation, who calls his mental model the Octopus Model.

Saurabh was recently interviewed by Vishal Khandelwal of Safalniveshak.com, in their monthly newsletter, Value Investing Almanack, of which I’m also a subscriber. Vishal was kind enough to allow me to republish the portion of the interview pertaining to the Octopus Model, as well as this beautiful illustration.

VK: We’re seeing rapid technological changes all around. You are at the forefront of these changes and you’re also an investor. Since you practice value investing, you also look at businesses from long-term perspective. How do you combine these two aspects in terms of things changing really fast and long-term investing? On one hand Mr. Buffett talks about the concept of sustainable advantages – moats which are sustainable, and on the other hand we are living in a world where most businesses are not looking sustainable. In such an environment, how do you combine the thoughts of investing when businesses are disrupted so fast beyond people’s imagination?

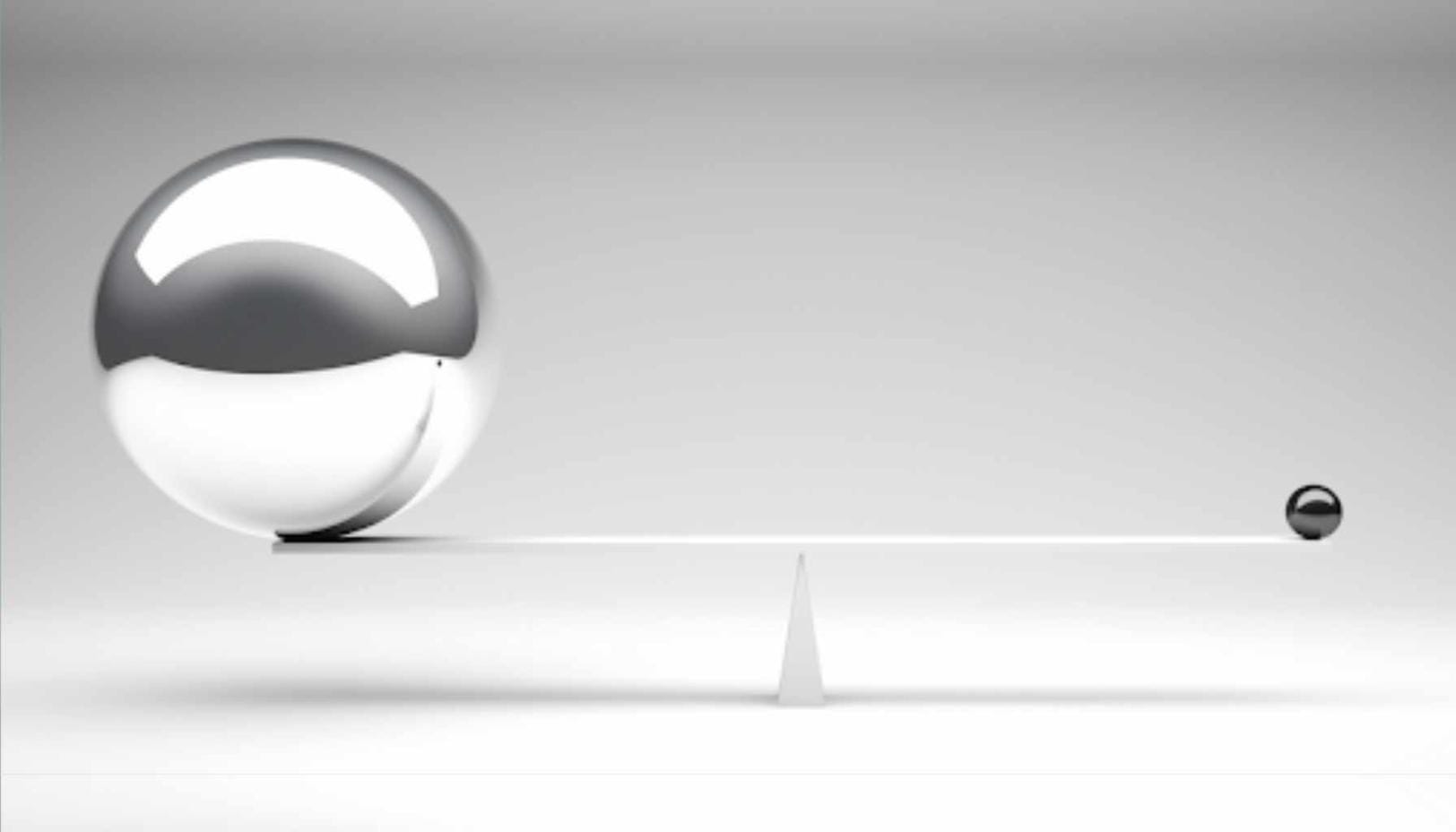

SM: I have a mental model that I call, for the lack of a better word, the Octopus Model. Let’s take a company which has a technology product, and because technology is prone to disruption, its shelf life is very small. This means any new technology can come up. And as you said, value investors stay away from the fact that a new company could come up any day and break this technology with a better one or a cheaper one. So, there is no moat as Mr. Buffett might say. Therefore, value investors typically would stay away.

Now let’s do a small thought experiment, in the spirit of Einstein. Let’s say that this company now has not one product of technology but a few products on technology. And it also reduces its profit margins. Instead of making a 20-30% profit margin, this company makes minimal profit margin. In our thought experiment, two things should happen. One, the multiple lines of products, if they are interrelated and reinforce each other, should start creating some sort of a competitive advantage. Second, the reduced margins. What do you think the reduced margins would do Vishal?

VK: I think low margins would create a barrier for new players from entering the market. If the incumbent is working and sustaining on lower margins, my understanding is that it creates a moat. In some way it inhibits competition because competitors are looking at industries with high profit margins and not challenging industries with low profit margin. So, this is what my understanding is. I am not sure if that’s right.

SM: Yes, you are right. If someone is making low or no margin, you must lose money to compete with them, assuming you cannot come up with a better technology. Moreover, if the number of technologies and products is more than one and they are related to each other, you must make three of them and lose money on three of them to compete with the incumbent. So, this adds some durability in an otherwise vulnerable situation. There is less incentive for competition to come and lose even more money. Now the shelf life, the lifetime of this company could be, probabilistically speaking, more than the previous company that we had talked about. Therefore, as a value investor it makes sense for you to at least try and look at it because its lifetime is going to be longer than a typical company, and that gives you the opportunity to invest in it at the right time.

The other thing I would add is the effect of scale on longevity. If you are delivering your product not just to one person but lots of people. You have a huge network and network effects start showing up in wonderful ways. A new competitor must first develop multiple products, then at low margin, then gather millions of users to compete with the incumbent. So there is some first-mover advantage beyond a critical mass. You can displace one product, one technology but to do it over all products, all interrelated technologies, across billions of users is going to take time and effort. You can still do it. It’s not impossible but base rates start declining.

Once a company has reached this, it can add an incremental line of product out of which it lights up profit margins. It starts making money. But this line of business is behind the first four or five lines of businesses that were basically low margin. Let’s think Amazon in this case. Amazon has very low (almost negative?) margin on Kindle devices. It gives free shipping to Prime Members, who also have free access to Prime video library and all sorts of other value-added services. But Amazon makes a ton of money on Amazon web services (AWS), on third party merchandise and on third party advertising.

You can see how these several lines of business where Amazon doesn’t make money help it attract and get a sticky customer base. This gives the same economies of scale where you add the Nth line of business and you can light it up with profits. If you were looking at Colgate, instead of looking at their annual revenue growth or profit growth what you should be focused on is that they have the shelf space across all the retailers and when they add a new line of product, let’s say a shampoo, even if they have spent 10- 20 million dollars researching it, the incremental returns on capital on that business are so huge. Because of the network and brand, other things take care of itself.

I call this the Octopus Model where all these lines are the reach of the octopus, building connections with the users. I feel this is one of the many patterns or mental models that as value investors one might want to have. Through your mental models you gain some insights, first or second order. Here we are not talking profit margin and linear growth and revenues. We are not doing any of that modelling. But we’re trying to get to an insight about the business that is not dependent on precise numbers, but could lead to a better predictive outcome than other quantitative models. If you have an insight like that in any business — we just used technology as an example because you asked me — I think that could differentiate you as a value investor.

VK: Wonderful insights, Saurabh. I can see delayed gratification here where a company is losing money across business, across different areas and because of which it’s inhibiting competition. But it’s willing to hold its ground and sustain business for few years to be able to see profits and then it’s a different story altogether.

Since you talked about Amazon, it reminds me of Jeff Bezos who mentioned that the only sustainable advantage that a business has is long- term thinking. If you are thinking in terms of 1 to 3 years, then you are thinking like everyone else. But if you are thinking in terms of 7 to 10 years, then you are thinking uniquely. It’s a very valid point that you made. My feeling is that it applies so well, not just to technology but to any industry, any promoter, any management who in an era of shrinking attention span and shortening business cycles is willing to think long term.

SM: Absolutely, and the other nice thing about this is what Mr. Buffett says, “The secret…is to sit and watch pitch after pitch go by and wait for the one in your sweet spot.” If I might add something to it – you can decide the time at which you are going to swing your bat. What I mean by that is there are various stages in the life cycle of the company that you just talked about. You very rightly connected it to delayed gratification which is the key here. If a company is building one product, one line of business and if you invested at that point and it did well, you’d make a ton of money. But a lot of such companies may not make it to the stage of the Octopus that we were talking about. You can even identify this pattern happening at a later stage. After the critical mass is reached, your margin of safety has gone up so much and your chances of permanent loss are so little that you can then decide to swing. So, you don’t have to swing at every stage of the game either. It is very interesting in that sense.

===> Interact and learn with 250+ of the best microcap investors on the planet. [Join Us]

MicroCapClub is an exclusive forum for experienced microcap investors focused on microcap companies (sub $500m market cap) trading on United States, Canadian, European, and Australian markets. MicroCapClub was created to be a platform for experienced microcap investors to share and discuss stock ideas. Since 2011, our members have profiled 1000+ microcap companies. Investors can join our community by applying to become a member or subscribing to gain instant view only access. MicroCapClub’s mission is to foster the highest quality microcap investor Community, produce Educational content for investors, and promote better Leadership in the microcap arena. For more information, visit http://microcapclub.com and https://microcapclub.com/summit/

Get Alerted to our Next Educational Blog Post

My intention is to hold stocks forever, but the harsh reality is every stock has different shelf life.

How does a business get a premium valuation when they sell a commodity?

It's often how you react (or don't) to the same situations that shows you how much you’ve grown.