Shelf Life

My intention is to hold stocks forever, but the harsh reality is every stock has different shelf life.

Some of the best investing opportunities I’ve found are when a microcap company has a problem or series of problems that seem insurmountable but there’s a sensible plan in place to solve them.

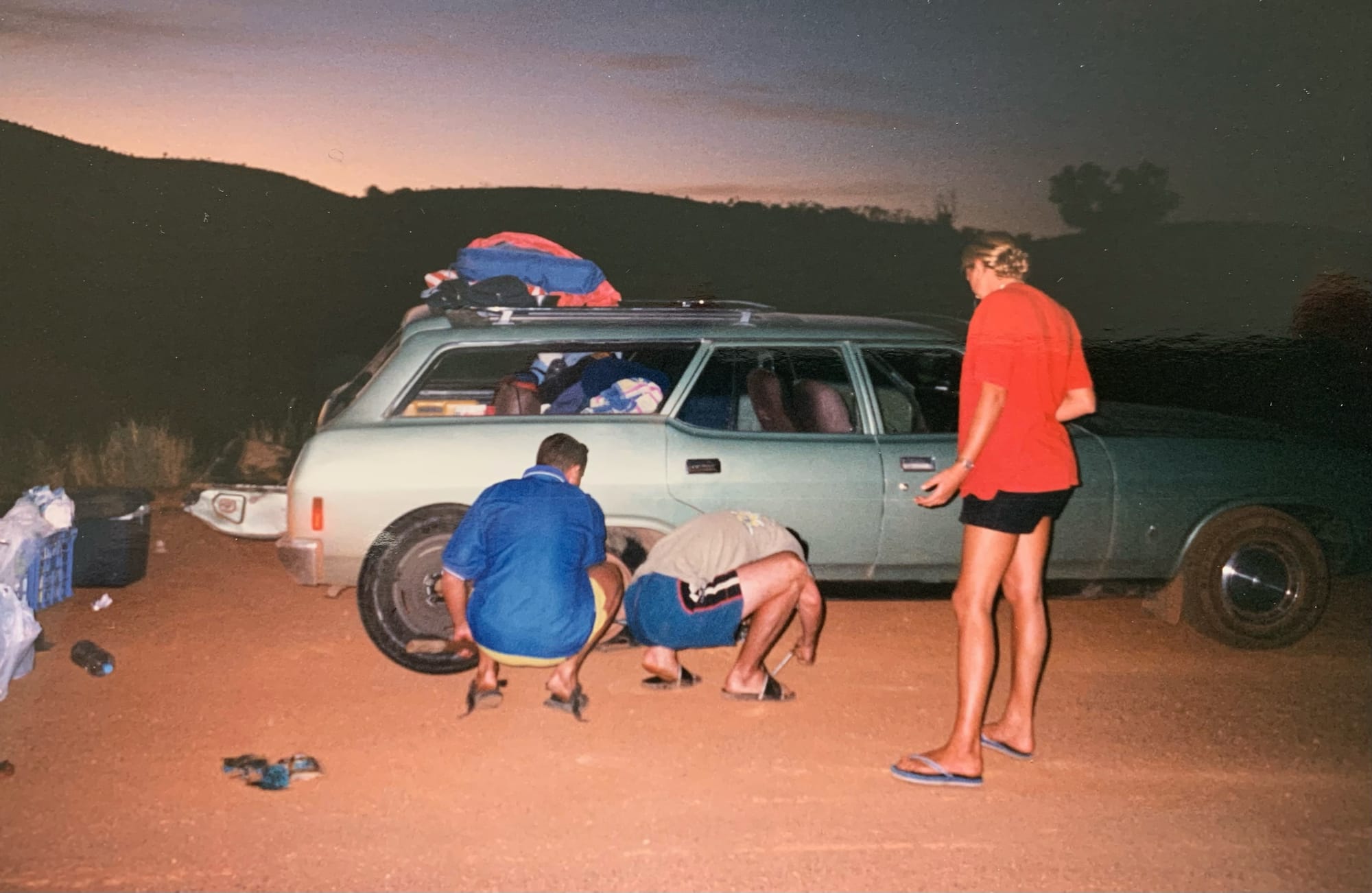

We were making our way up the west coast of Australia with a short stop in Perth when the car was stolen. I nervously reported the theft to the police, and they said they’d be sure to let me know as soon as there was any update. When I hadn’t heard anything after the end of the first day, I started to panic, thinking this might put a major kink in our travel plans.

Four months earlier, I had gotten an email from my friend Greg. “Hey dude, I’m in Cairns and found us a car. It’s a lime green Ford Falcon station wagon. It’s twenty years old but it’s a beauty. I took it for a test drive and the mechanic said it’s in great shape. $3,000. Let me know if you’re good with paying half and I’ll buy it.”

It sounded perfect, so I gave him the green light. A month later, on January 2, 1999, I hopped on a plane and made the twenty-hour journey from Canada to Australia, and it was the start of a six-month long road trip around Australia with Greg.

The first problem we noticed with the Falcon was on our first long road trip. We pulled over for a short lunch break, and when we tried re-starting the engine, it wouldn’t turn over. We finally got it started after twenty minutes. After this happened a few more times, we learned that anytime the Falcon overheated, it stalled like this.

There were other problems that showed up. The Falcon started to have trouble climbing steep hills and we discovered that the accelerator cable needed replacing. Then the tailgate door started sticking. And there were several more problems including multiple flat tires because they just weren’t built for the rugged outback roads we were driving on.

Back to the theft of the Falcon. After waiting anxiously for a full day, I finally got a call from the police telling me they had found our car parked a few blocks away. When I went to pick it up, there were two things I noticed that were different about it - there was a small triangle shaped window on the driver’s side that was broken. And the oil dipstick was sitting on the front seat.

I asked the police officer why the oil dipstick was there, and he said, “Mate, that’s what they used to start your car to take it for a joyride. Everybody knows you can start a Ford Falcon with a dipstick.”

I didn’t know that and we had owned this car for four months.

We finally arrived back in Cairns in July after driving a full loop around the country. It was time to part with the Falcon and we put it up for sale. A young backpacker from New Zealand who was starting his own journey around Australia bought it, and we informed him about all the problems we had. I’m sure he discovered several more during his ownership. That’s how it is with used cars – they all have problems.

Investing in microcap companies is similar to owning used cars in this way - all microcap companies have problems and things are always going wrong. Even with the good ones. The problems might be things like:

Running a business can be brutally hard. Sometimes as investors, we don’t appreciate that from our perch. But problems are always boiling over in businesses.

Some of the best investing opportunities I’ve found are when a microcap company has a problem or series of problems that seem insurmountable but there’s a sensible plan in place to solve them. I’d like to tell you about one of these situations that I invested in several years ago.

It was early 2009, right in the thick of the financial crisis and I was researching a company called The Brick Group Income Fund. At the time, the Brick Group was one of the largest retailers of furniture, electronics and appliances in Canada. They had a strong brand and a network of 230 stores called “the Brick”. I had shopped there occasionally and had heard the company jingle “nobody beats the Brick” hundreds of times.

But after decades as a thriving retailer, the Brick ran into problems starting in early 2009. The economy was crashing and consumers were hunkering down. There were operational problems caused by poor decisions by previous management that resulted in same store sales declines that were three times worse than their publicly traded competitors Leon’s furniture and BMTC. They had recently cut their dividend. And to top it off, they were on a path toward defaulting on their senior debt at the worst possible time.

The founder of the Brick, Bill Comrie, stepped out of retirement to help navigate the company through this mess. First, the debt problem was fixed through a debt restructuring in June 2009. Then in July, Comrie helped recruit a new CEO named Bill Gregson who had previously turned around another retailer named Forzani Group, owner of the largest sporting goods chain in Canada. To attract Gregson to take over the mess at the Brick, he was granted a heap of stock options that would only pay off if he was successful.

Gregson thought that by returning to merchandising basics, they could fix the mess. To do this, he proposed a four-point plan:

The stock price had dropped from a high of $15 to a low of $0.60 and the company was being thrown in the dumpster valued at $60 million. Although there was also some debt, this was a company that had done $1.4 billion in annual revenues and $80 million in EBITDA prior to the recession. There was risk, but Gregson’s plan made sense and if they could return to anywhere close to their performance prior to the recession, I thought the stock could be a home run.

I chose to make my bet through warrants that had been issued as part of the debt restructuring. The warrants gave holders the right to purchase shares at $1.00 at any time over the next five years. I thought five years would be plenty of time to see the Brick sink or swim. If it failed, it wouldn’t really matter if I owned the common stock or warrants. But if they pulled it off, the warrants could really juice my returns. I was able to build a 5% position size in the warrants.

Within a month of Gregson taking over, the company started rehiring sales associates. And Gregson had negotiated increased borrowing capacity from their lender to pay for inventory. All suppliers had been repaid in full and he met with each one of them and convinced them to restock the Brick’s warehouses. Sometimes a CEO’s most important job is creating a sense of confidence in their company.

As 2009 progressed, you could see the strategy was working. Gregson made a few key hires to build out his team and you could see the sales, margins and profitability improving each quarter. He was doing exactly what he said he would do.

By 2010, the Brick Group was almost back to pre-crisis levels of revenue and exceeded pre-crisis levels of profit. Their results continued to improve into 2011 when Gregson stepped down from his CEO role. He had fixed all the problems and the company was now leaner and stronger than its previous best years. The stock had quadrupled from $.60 to $2.40 over the period he was CEO and he was rewarded with the vesting of 6 million performance-based stock options.

So how did the warrant investment work out? I sold them all for between $1 and $1.50 on an average cost of $0.22 which I was ecstatic about. Unfortunately, I left a lot of gains on the table. If I had held until the Brick Group was acquired in 2012 for $5.40 a share, I would have had a 20X gain. But I was still happy with the outcome.

To get back to the used car analogy, the lesson I learned is to always be on the lookout for microcap companies where there’s been a change of the driver (management) and the engine’s been replaced (new strategy), but still priced like a clunker ready for the scrapyard. Look for companies with difficult problems like the Brick Group had, and capable management with a sensible plan to fix the problems. Because the great management teams are able to solve problems that look nearly impossible to everyone else.

MicroCapClub is an exclusive forum for experienced microcap investors focused on microcap companies (sub $500m market cap) trading on United States, Canadian, European, and Australian markets. MicroCapClub was created to be a platform for experienced microcap investors to share and discuss stock ideas. Since 2011, our members have profiled 1000+ microcap companies. Investors can join our community by applying to become a member or subscribing to gain instant view only access. MicroCapClub’s mission is to foster the highest quality microcap investor Community, produce Educational content for investors, and promote better Leadership in the microcap arena. For more information, visit https://microcapclub.com/ and https://microcapclub.com/summit/

Get Alerted to our Next Educational Blog Post

My intention is to hold stocks forever, but the harsh reality is every stock has different shelf life.

How does a business get a premium valuation when they sell a commodity?

It's often how you react (or don't) to the same situations that shows you how much you’ve grown.